Two (three really) exhibitions on Fascism

As a special summer treat, we went to some exhibitions about Fascism. Here’s what we learnt.

Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919-1933 at Tate Liverpool

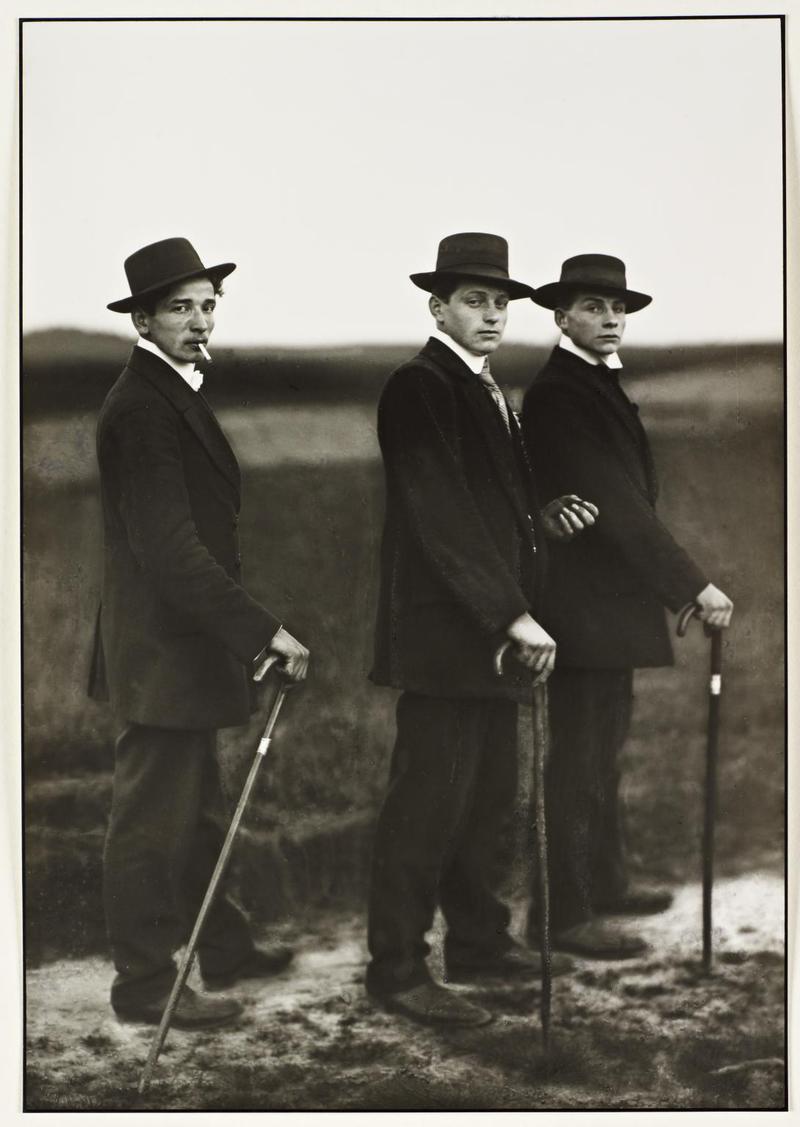

Portraying A Nation starts with August Sander’s black and white photos tracking the Weimar republic up to the rise of the Nazis. I’d seen some of his better known works - the bricklayer, the farmers on the way to the dance - but didn’t know anything about the scope of his works - portraits of the state of the nation, cataloguing every type of person in Germany, in categories rather reminiscent of an old-fashioned encyclopedia, like “The Skilled Tradesman”, “The City” and “The Last People” - this last being the marginalised, the elderly, the disabled. Capturing the world as it is constitutes a radical, progressive act, and his work was of course eventually banned by the Nazis.

But this exhibition doesn’t group the portraits by category, but rather chronologically. This seems like an odd choice as you first start the circuit. Historical tidbits are written on the walls above the photos, which we skimmed on the first time around, but it’s fascinating to see how the threads of both progressive, hopeful politics - the recognition of worker’s rights, education, democracy - coexist with the rise of the Nazis, xenophobia, pogroms. It feels like a mirror of our times - progress in social attitudes, with a regressive backlash, and everything hangs in the balance. And of course, the chronological view pays off in the last room when you see that the rise of Fascism happens slowly, so very slowly, until it happens, at which point it happens very quickly indeed.

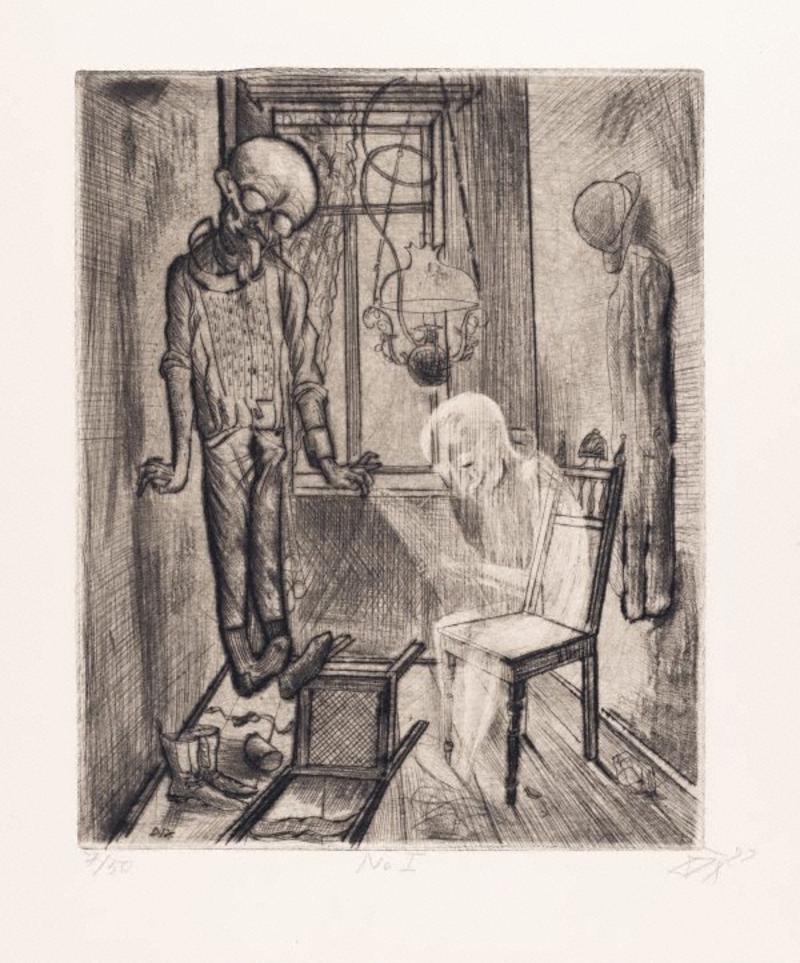

The Otto Dix section is fabulous. It’s varied, from lively watercolours to the large scale, rather cold egg tempera paintings, but perhaps the most interesting part is his printmaking. Of his early ones, I loved this very sinister one - “Selbstmord, 1922 (The Suicide)” - and stared for ages at it trying to work out how it’s done.

But his later War Etchings - filling up a whole room - are fabulous. He’d mastered acquatint (to the point where comparisons with Goya’s “Los desastres de la guerra” are everywhere) and plays with so many techniques and varied effects of light. One of the pieces looks like a breathtakingly beautiful nature scene with its subtle textures of stone and plant: as you stare at it, the textures coalesce and form into new details, a leaf, water running over rock, one prone body, then another (soldiers sleeping in a trench? or piled up corpses?)

This show is great, and I’d have loved to have bought the catalogue - but the Tate don’t put their A-team onto the buying or publishing teams for their not-London shows: disappointing reproductions, and explanatory text in a sans-serif font, in red. I kept picking the book up, hoping that I could stomach it, but I really couldn’t. I’d have loved to throw money at the Tate for this, but sent it to a second hand book dealer in Germany for a catalogue of the “Der Krieg” exhibition instead.

(On till 15th October 2017, you should go)

Wyndham Lewis at the Imperial War Museum

So we got very excited because Mark E Smith of the Fall was going to do a talk at the IWM’s Wyndham Lewis exhibition including “a performance of speeches, poems and ramblings”. Sadly, MES had to cancel due to ill health, so we missed the ramblings, but as the museum had offered a refund but also free tickets to the exhibition, we went to see it anyway, with some misgivings.

Why misgivings? Well, Lewis has an unsavoury reputation because he was a racist, an anti-semite, a misogynist, a homophobe, and supported Nazism for a decade, writing the first book published in UK about Hitler, praising him as a “man of peace”. Now there’s much more to write about Lewis, but charitably, with a prevailing wind, it’s a fairly important starting point. In 2017 when the KKK is in the White House and the Nazis are back in the Reichstag, it’s pretty much vital.

But I like those paintings I’ve seen, and was prepared to give the exhibition the benefit of the doubt (and I’m not arguing that it should have been “censored” out of some left-wing prudery.)

So, on the plus side:

- there’s a wider range of works than I’d seen before:

- his early, lively draughtsmanship

- paintings from his time as official war artist (imagine Paul Nash, if he could draw people)

- the Vorticism and Tyros etc. that he’s best known for

- rather beautifully observed portraits (his style influenced Bacon and others)

- later historical paintings

Also, some of the curatorial notes are intriguing, such as on the details of his various beefs with the Slade school, rival artistic factions and so on. Some of his points are perfectly valid - the well-heeled Bloomsbury group did hide out in villages to further their artistic careers and reputations while he risked his life and damaged his career in serving in the war.

But as I said it’s 2017, and increasingly the whole pointed refusal to deal with the Elephant In The Room builds up. Let’s start with the name, “The Original Rebel Artist”, and all the copy introducing the exhibition which is focused on the bigging up his talent and his position as an “anti-establishment maverick”. This could be a fascinating comparison with the bright young men of the Alt Right and Gamergate: Lewis could be a fascinating study for that vital question “How do these young men become radicalised?” but it seems to be taken at face value.

About midway through, we learn that Lewis repudiated his enthusiasm for Hitler and Anti-Semitism in 1939, when everyone else was doing it too. So that’s nice. Was his contrition sincere? Did the piece get as much publicity as his pro-Nazi work (public and private) in the previous decade? How did he behave and what did he espouse afterwards? Again, in 2017 we could learn lessons from talented and charismatic cultural figures supporting or tolerating Fascism on their platforms: does denying your beliefs a decade later when you realise they’re damaging your media career succeed in whitewashing your reputation?

In the final room, some academic talking heads discuss Lewis, and justify the fact that they’ve spent their careers studying him. Obviously they have to justify their interest, to themselves and their grant sponsors, and it’s at least partly fair to argue as they do that we should look at the primary sources before jumping to (critical) conclusions. So why does this, a major retrospective, singularly fail to show those sources? Where are the critical voices (contemporary and current) condemning Lewis’s abhorrent views?

So, putting it charitably, the decision to glorify Lewis as a “Rebel”, and to not properly grapple with the thorny issues, or even clearly state them (I summarised them in a sentence at the start of this piece, so it can be done), is at the very best lazy and craven. Deciding what to focus on with your cultural capital and platform is an important question. What a museum with the words “Imperial” and “War” in its name decides to showcase with its money, time, and resources is an important question. It’s not cultural censorship to suggest that now, in 2017, this exhibition is a disappointing answer.

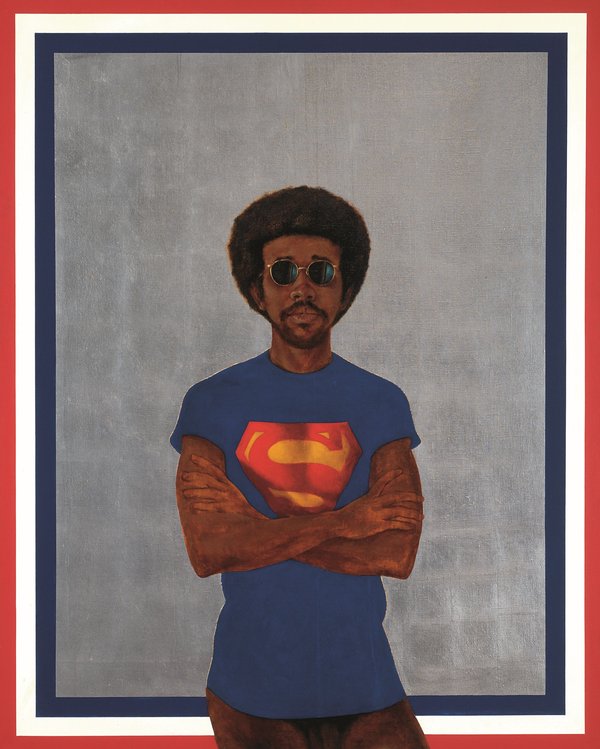

Art in the Age of Black Power at the Tate Modern.

So by way of contrast, try Art in the Age of Black Power, which uses the resources of a powerful cultural institution with a complex and problematic history to put Black American art from the height of the Civil Rights movement centre-stage. This is a superb and timely decision.

We were fortunate to turn up on a Friday evening late: it’s surely no shocking revelation that the demographics of major art exhibitions at the Tate tend towards the middle-aged, middle-class, and white, so seeing the “typical gallery-goer” (including us, kinda) realise that they had to check their privilege in a space thronged by young black men and women was a glorious change of dynamic.

Peoplewatching aside, the exhibition is good, really really good (we were at the Tate for the Giacometti, but were so excited by this show that we saw it twice.) Perhaps the opening few rooms pack the largest emotional punch but the show sustains interest throughout.

(On till Oct 22nd 2017, you should go.)